The Earth is experiencing an unprecedented decline in biodiversity at a scale not seen in human history. Scientists warn that around one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades. This rapid loss far exceeds the normal background extinction rate, indicating that we may be entering a sixth mass extinction event driven by human activities. From iconic mammals and birds to lesser-known amphibians, insects, and marine life, virtually all major groups are affected.

The urgency of the crisis is underscored by stark statistics and trends: wildlife populations have plummeted worldwide, notably right from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and extinctions are accelerating at an alarming pace. This report provides a comprehensive, data-driven summary of the global decline of species across taxonomic groups, drawing on authoritative sources (IUCN Red List, IPBES, WWF, UN, and peer-reviewed studies) to illuminate the magnitude and speed of biodiversity loss. The goal is to rigorously frame the scale of the problem – through hard data, historical trends, and projections – as a foundation for understanding why any solutions must match or exceed this magnitude in order to be effective.

Historical Extinction Trends (1500–Present)

Human impacts on nature have driven a wave of extinctions in the modern era. Since the year 1500 AD, at least 905 species are known to have gone extinct worldwide. Paleontologists estimate that under natural conditions (without human interference), such a number of extinctions would have taken millennia to occur, not just a few centuries. The fossil record suggests a background extinction rate on the order of ~1 species per million species per year, but today’s rates are orders of magnitude higher. In fact, experts estimate that current extinction rates are 1,000 to 10,000 times the natural background rate, meaning we are losing species much faster than new ones evolve.

The timeline of recorded extinctions shows an acceleration in recent centuries: comparatively few extinctions were documented in the 1700s and 1800s, but the 20th century saw a sharp increase in species losses. (For example, the extinction of well-known species like the dodo (late 17th century), Steller’s sea cow (18th century), and the passenger pigeon (1914) marked the beginning of this trend, which intensified throughout the 1900s.) According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), at least 680 vertebrate species have been driven to extinction since 1500 – a number that climbs well into the hundreds when including invertebrates and plants, reaching the ~905 figure noted above.

Crucially, these tallies are likely underestimates, since many species (especially small or poorly studied ones) may have vanished without ever being recorded by science. In short, the past 500 years – and especially the post-Industrial Revolution era – have seen an anomalously high wave of extinctions, signaling a biodiversity crisis in motion.

The Current State: Thousands of Species at Risk

Today, an enormous number of species are teetering on the edge of extinction, even if they haven’t vanished yet. The IUCN Red List – the global authority on species conservation status – has assessed over 157,000 species to date, and finds that roughly 28% (more than 44,000 species) are threatened with extinction under current conditions. “Threatened” status includes Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered species – those facing high to extremely high risk of extinction in the near future. This highlights that the extinction crisis is not just about the species we’ve already lost, but the much larger wave of species declines underway.

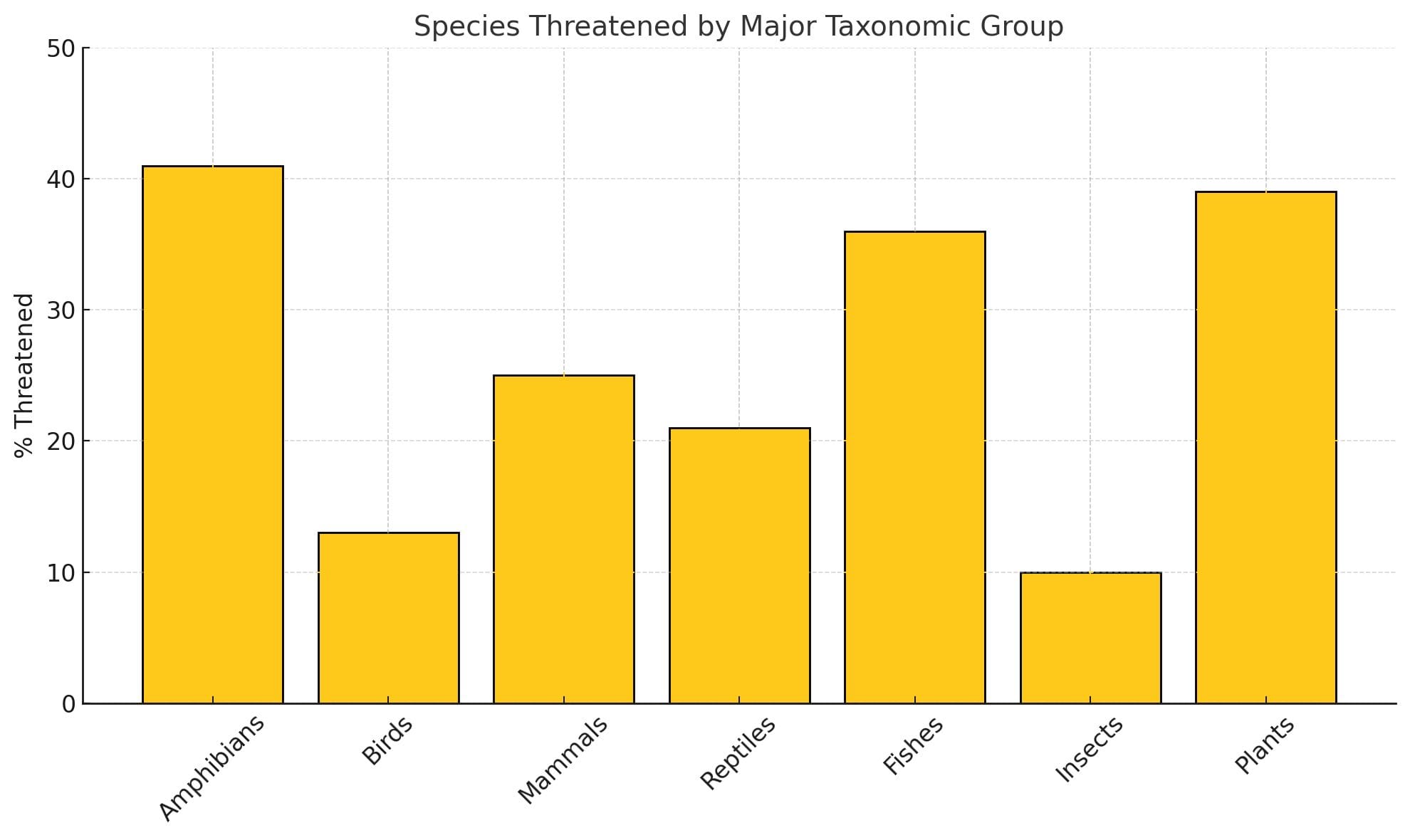

Percentage of species documented as Extinct (EX) or Threatened (Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU)) by major taxonomic group, as of the December 2023 IUCN Red List. Amphibians have the highest share of species at risk (over one-third of known amphibian species are in these threatened categories), while groups like insects show a seemingly tiny fraction threatened – a likely underestimate given that most insect species have not been assessed.

Not all groups are equally imperiled – amphibians, coral reefs, and certain marine animals are among the hardest hit. According to the global assessment by IPBES, more than 40% of amphibian species are threatened with extinction, making them the most at-risk class of vertebrates. Amphibians (frogs, salamanders, etc.) have been decimated by a combination of habitat destruction, climate change, and diseases like chytrid fungus, such that nearly half their diversity is in jeopardy. Reef-building corals are similarly imperiled – about one-third of reef corals are threatened, reflecting the crisis facing coral reefs from ocean warming, acidification, and pollution. And more than one-third of all marine mammals (such as whales, dolphins, seals) are threatened as well, due to factors like overfishing (which depletes their prey), entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes, and climate-related shifts in ocean ecosystems.

Terrestrial and avian groups, while comparatively less threatened in percentage terms, are still in serious decline: for example, roughly 25% of mammals and 13% of birds are classified as threatened globally. Even the insect world – which comprises millions of species – is showing worrying signs: although only about 10% of insect species evaluated are listed as threatened, evidence from regional studies (e.g. dramatic drops in insect biomass in Europe) suggests many insect populations are collapsing, implying a potential “insect apocalypse” that is not fully captured by current assessments.

In summary, a very large swath of life on Earth – from charismatic large animals to tiny invertebrates and plants – is either already endangered or in decline. The “barometer of life” is flashing red: tens of thousands of species are at risk, and without intervention many will likely go extinct in the coming decades.

Wildlife Population Declines: Beyond Extinction Counts

Extinction counts alone do not tell the whole story of biodiversity loss. Another critical metric is the decline in abundance of surviving species. The WWF’s Living Planet Index (LPI), which tracks population trends in thousands of vertebrate wildlife populations worldwide, reveals an astonishing collapse in wildlife abundance.

According to the latest analyses, monitored wildlife populations have declined by an average of ~69% since 1970. In other words, global vertebrate populations today (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish combined) are less than one-third the size they were 50+ years ago on average. This index, based on over 30,000 populations of more than 5,000 species, is a robust indicator of overall ecosystem health.

The decline has not been uniform: some regions and ecosystems have suffered even steeper drops. For instance, Latin America (including the Amazon and tropical Andes biodiverse regions) shows the most catastrophic trend – a 94% average decline in wildlife population abundance since 1970. Similarly, freshwater species (those living in rivers, lakes, and wetlands) have seen global populations plunge by about 83% on average – the largest drop of any broad ecosystem type.

These numbers paint a grim picture of ecosystems in crisis: even species that are not yet extinct are often a shadow of their former abundance, which can disrupt ecological functions (pollination, seed dispersal, food webs, etc.) long before the last individual vanishes.

The Living Planet Report underscores that we are not only losing species outright, but also overall wildlife abundance at an alarming rate. To put it another way, Earth’s biodiversity isn’t just experiencing a few high-profile extinctions – it is undergoing a pervasive biological annihilation in which populations everywhere are thinning out or collapsing.

This widespread decline in numbers is a prelude to extinctions (fewer individuals make species more vulnerable), and it also diminishes the resilience of ecosystems even for species that persist.

Drivers of Biodiversity Loss: The Perfect Storm

What is causing this global collapse of species? Research consistently points to five direct drivers of biodiversity loss, all of them driven by human activities:

- Habitat destruction and fragmentation (Land/Sea Use Change)

The conversion of natural ecosystems into agriculture, urban areas, infrastructure, and other human uses is the leading cause of terrestrial biodiversity loss. Humans have significantly altered 75% of Earth’s land surface and about 66% of the marine environment, often replacing rich habitats (like forests, wetlands, coral reefs) with monocultures or built environments that support far less life. Deforestation, draining of wetlands, and coastal development all fall in this category. The more habitat we destroy or fragment, the less space and resources remain for wild species. - Direct over-exploitation of organisms

Over-hunting, over-fishing, and over-harvesting of wild species is the second major driver. Many species have been driven to endangered status by unsustainable use – from the overfishing of the world’s oceans (about 34% of global fish stocks are overfished as per FAO reports) to the poaching of iconic animals (like elephants for ivory, rhinos for horn) and unsustainable logging of timber species. Exploitation has had devastating effects especially on larger, slower-reproducing animals. For example, the hunting-driven extinction of the great auk and pressure on pangolins and big cats illustrate this driver’s impact. - Climate change

Although habitat loss and exploitation historically were the biggest factors, climate change is rapidly climbing as a threat. Since 1980, global greenhouse gas emissions have roughly doubled, raising average temperatures by at least 0.7 °C and already altering ecosystems and species ranges. Many species now face shifting or shrinking habitats as temperatures rise, sea levels increase, and weather patterns become more extreme. Climate change has been identified as a key driver behind coral bleaching (mass die-offs of corals in overheated waters), disruptions to migratory routes, and the “escalator to extinction” effect in mountainous habitats (where species are forced upslope until no habitat remains). Importantly, climate change’s impact is expected to surpass habitat loss as the largest driver of biodiversity loss in coming decades if warming continues unabated. Without aggressive mitigation, climate change could become the single biggest catalyst for extinctions in the 21st century. - Pollution

Various forms of pollution – plastic pollution in oceans, chemical pesticides and fertilizers, industrial runoff, oil spills, air pollution, etc. – are directly harming species and degrading ecosystems. For instance, pesticides contribute to insect declines; excess nutrients cause dead zones in aquatic systems; and plastics ensnare or are ingested by marine wildlife. Pollution often works synergistically with other threats (e.g., making habitats unlivable or organisms more susceptible to disease). - Invasive alien species

The introduction of non-native species to ecosystems (whether intentionally or accidentally by humans) is the fifth major driver. Invasive species can outcompete, prey upon, or bring diseases to native species that have not evolved defenses. Examples include invasive predators like rats and cats decimating island bird populations, the chytrid fungus (likely spread by human activity) devastating amphibians, or pest plants overtaking native flora. Globalization has greatly increased the spread of invasives, adding pressure to ecosystems already weakened by other drivers.

These direct drivers are underpinned by indirect drivers such as human population growth, overconsumption, economic incentives that undervalue nature, and weak governance. The result is a perfect storm for biodiversity. For example, tropical deforestation (habitat loss) often happens to produce commodities for global markets (consumption patterns), while climate change (driven by fossil fuel use) further stresses the species in those shrinking forests – an interplay of multiple factors.

The recent Global Assessment Report (2019) from IPBES concluded that human activity has “significantly altered” three-quarters of land and two-thirds of ocean ecosystems, and that current negative trends in biodiversity will undermine 80% of the Sustainable Development Goals related to poverty, food, health, water, cities, climate, oceans, and land. In sum, the biodiversity crisis is a systemic result of how our societies are interacting with the planet’s natural systems, and all these drivers must be addressed to halt and reverse the decline.

Future Outlook: Projections and the Need for Transformative Change

What does the future hold for global biodiversity? If current trajectories continue, the projections are dire. Recent modeling studies that account for habitat loss, climate change, and ecological interactions predict a substantial further loss of species in the coming decades. For example, a 2022 study using a “virtual Earth” simulation found that under a mid-range scenario (roughly following our current policies and emissions), about 6% of all species will be gone by 2050, rising to 13% by the end of the century.

In a worst-case, high-emissions scenario (with severe climate warming and continued habitat destruction), the model estimated up to 27% of species could disappear by 2100. Other assessments concur that we risk losing a quarter or more of Earth’s species by 2100 if we fail to change course. In contrast, scenarios where humanity takes aggressive action to protect nature show much better outcomes. If we drastically curtail habitat destruction and limit global warming (e.g. keeping climate change to the Paris Agreement target of 1.5 °C), extinction risks drop dramatically – one analysis finds that only around 1.8% of species might face extinction by 2100 in a 1.5 °C world, compared to the much higher losses under status quo development.

These scenario comparisons underline a crucial point: the future of biodiversity is very much in our hands. The difference between a mass extinction and a relatively preserved biosphere hinges on actions taken in the next few decades.

Encouragingly, the same IPBES report that sounded the alarm also emphasizes that it is not too late to make a difference, but only if we undertake “transformative change” across economic, social, and political systems. Incremental efforts are simply not enough given the scale of the challenge. To bend the curve of biodiversity loss, conservation actions must be ambitious and coordinated globally – protecting and restoring large areas of intact habitat, sustainable management of resources, curbing greenhouse gas emissions rapidly, controlling invasive species, and reducing pollution. There are success stories (from species brought back from the brink, to large-scale habitat restorations), but these need to be scaled up massively. The Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in 2022 (the “Kunming-Montreal” agreement under the UN CBD) aims to protect 30% of Earth’s land and sea by 2030 and take other bold steps, reflecting the kind of magnitude required.

In conclusion, the data are unambiguous about the magnitude and speed of biodiversity decline: the planet is losing species and abundance at an extraordinary rate, cutting across all forms of life and all regions. This is a crisis on par with climate change in its urgency and scale – indeed, the two are deeply interlinked. Framing the problem in rigorous terms, as we have done here with statistics and trends, makes clear that solutions must be commensurate with the challenge. Half-measures or business-as-usual trajectories will lead to an impoverished planet, whereas truly transformative, global action offers a chance to stabilize and even recover biodiversity over time.

The stakes could not be higher: the very fabric of life on Earth, the “web of life” that supports human civilization, is at risk of unraveling. Averting a mass extinction event will require unprecedented commitment and collaboration – a concerted effort to exceed the magnitude of biodiversity loss with an equally massive conservation response. Only by matching or surpassing the scale of the problem with the scale of our solution can we hope to secure a sustainable, nature-rich future for generations to come.

References:

1. IUCN Red List, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity

2. Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Global Assessment

3. WWF’s Living Planet Report

4. UN Global Biodiversity Outlook

All numerical statements and claims are backed by these sources as cited above. The evidence overwhelmingly points to a global biodiversity crisis that is both acute and chronic – a grand challenge of our time that demands science-based, large-scale solutions.